Richard Linklater and appreciating the little things

Halfway through Everybody wants Some!!, Richard Linklater’s raucous college flick about nothing in particular, baseball jocks romp around a Cotton-eyed Joe country bar, drunk on Lone Star beer and the easy bliss that precedes syllabus week. In the center of the melee, a freshman pitcher confides to his senior counterpart about the lonesome pressures of the mound. The senior takes a drag from his pool cue hand and responds.

“You know what, it’s scary up there on the bump. You’re all alone. It’s tough. But you get over that. You stop being who they want you to be, and you start being yourself. And when you figure that out, man, that’s when it really starts to get fun.” (I’m paraphrasing here.)

There, surrounded by drunken sophomoric revelry, is a defining Linklater moment. It’s surreptitious, barely heard over the din of the party, a moment of repose in the Texas night when Linklater allows his characters a heightened moment of realization. This is one of the benefits of Everybody wants Some!!, that in the midst of the bacchanalia and the booze, we get philosophical enlightenment. I suppose it maps fairly well to the college experience.

Across his filmography, Linklater uses these heightened moments as a means to articulate and convey what is his core message as a writer: life does not contain the dramatic turns of fictional narrative, and, if we expect it to, we miss those unexpected, mundane moments when we connect with others and discover something of our own nature.

To illuminate these moments, Linklater dampens the traditional narrative devices of mainstream cinema and, in doing so, evokes a sense of realism that helps his audience appreciate the little things.

Linklater and Plot

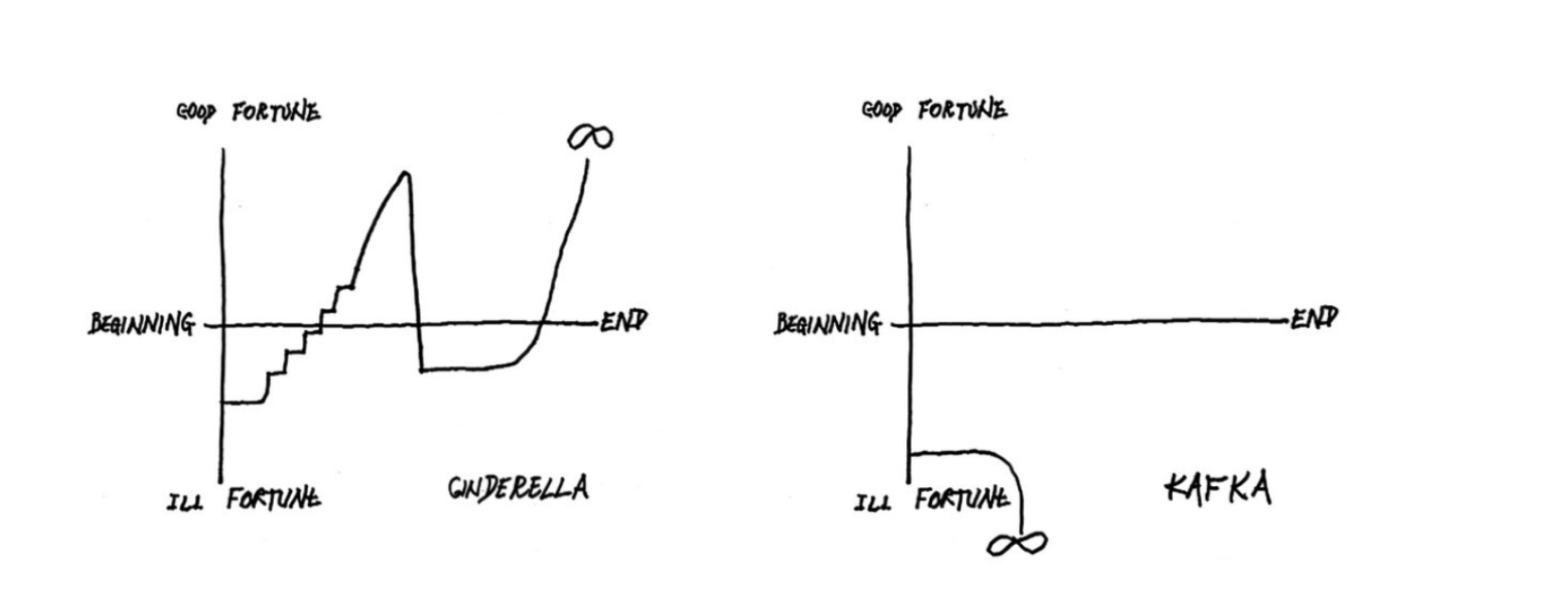

In his early movies, Linklater cast aside the typical plot structure in which a protagonist starts somewhere on the spectrum of fortune and, by the end of their story, has either significantly bettered (Cinderella) or infinitely worsened (Kafka) their position.

In his early work, Linklater takes the traditional story arc and flattens it out -- these are the movies that gave Linklater his reputation for stories where “nothing really happens.”

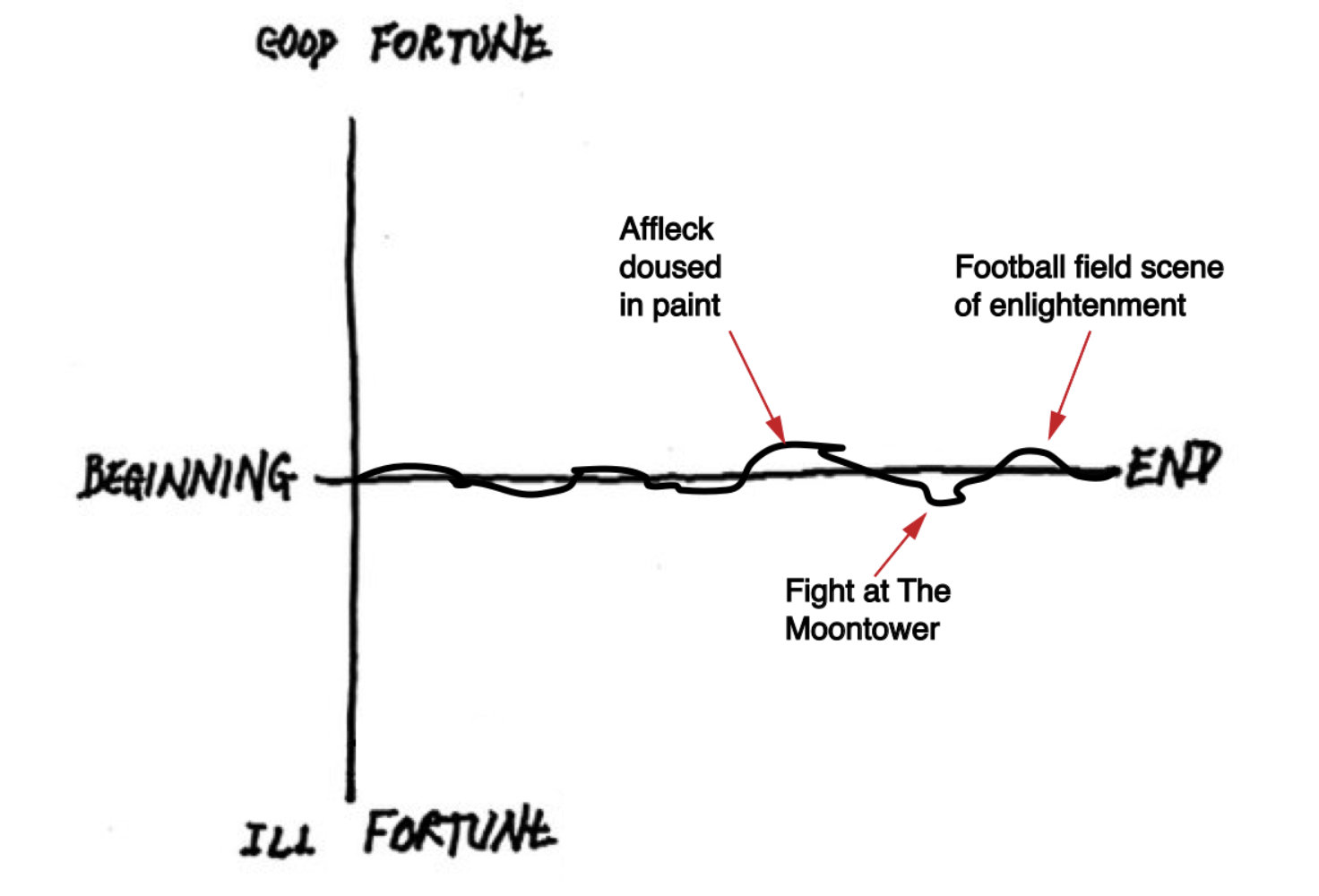

Dazed and Confused is probably the best example of this. Like Everybody wants Some!!, it follows a group of friends, doing not much else besides enjoying their time together. Here’s a hypothetical plot line for Dazed and Confused, as Vonnegut might have drawn it on the blackboard.

The plot of Dazed and Confused as told through Vonnegut's shape of story lens.

Dazed and Confused is an easy-going, entertaining movie, but the reason it’s had such staying power is because of its heightened moments. Sprinkled throughout its idling plot line of botched house parties and senior hazing are the same dashes of wisdom that we find across Linklater’s work:

“I'd like to quit thinking of the present, like right now, as some minor, insignificant preamble to somethin' else.” -- Cynthia, red-headed object of Wooderson's affection.

Linklater and Time

On the other end of the spectrum are those Linklater movies that challenge the viewer’s perception of time.

Before Sunset is a great highlight. The entire movie, a romance of two former lovers, Jesse and Celine, spending an afternoon together in Paris, is done in real-time.

Jesse, the film’s male protagonist, is in Paris on business. As his impending return flight looms, every minute that passes for the viewer is a real minute taken away from the couple on screen. Through the sole construct of real-time narrative, Linklater takes a fairly pedestrian conversation between two old friends and turns it into something dramatic and important.

In the film’s last frame, with Jesse waiting for his cab at Celine’s apartment, Celine dances to Nina Simone’s “Just in Time” as the screen fades to black. It’s another Linklater moment. Subtle, unexpected, and character-defining. From the New Yorker’s 2014 feature on Linklater:

The ending isn’t merely trite, because, like much of Linklater’s work, it has a sharp, against-the-system edge. Aren’t those heightened moments, the perfect instants with Nina Simone playing, the points toward which all life strains? Is it actually so crazy to set our compass by them?

By making time the sole driver of narrative, Linklater draws his characters closer to realism and illuminates these "heightened moments."

“You Make Realism Fun”

Across all of Linklater’s movies, we see one constant: a diminished sense of conflict and drama. Linklater casts aside these narrative norms to highlight the banality of everyday life and the importance of finding meaning within it.

But, knowing all of this, what can we do in the time between those rare, heightened moments?

In Everybody wants Some!! the answer is simple. Have as much fun as possible. And that’s the thing about Linklater’s movies. In spite of their philosophical ambitions, they somehow still manage to be a really good time. Throughout the duration of Everybody wants Some!! we get locker room scenes, a brutal game of knuckles, an axe through a baseball, jocks at a theater party, and other doses of rad that flood the college cortex with wild nostalgia.

It’s all a ton of fun, but in the closing scene of the movie, Linklater (never the one to leave a movie without imparting something of meaning) etches the portentous adage “frontiers are where you find them” into a blackboard.

In response, Jake, the movie’s protagonist and audience proxy, turns away his head, closes his eyes in sleep, and smiles. Whether in ignorance of the aforementioned frontiers or in eager ambition of finding them, we don’t know.

Jake may have just missed his own “heightened moment.” Luckily, he lives in the Linklater universe. There are likely more to come.